Making your own realtime audio AI training environment

This post is pretty specific, but I haven’t seen anyone else really write about it. So I hope this is helpful to the 20 people in the world that need it (ha!).

At VJLab, we train realtime (causal) audio models that understand and listen to music like a human does for use by visual artists in live concert settings.

This means our models have to be very fast, robust to noise, and accurate.

I’ll share some best practices we’ve found for setting up our environment and avoiding disaster.

💻 Our development & training environments

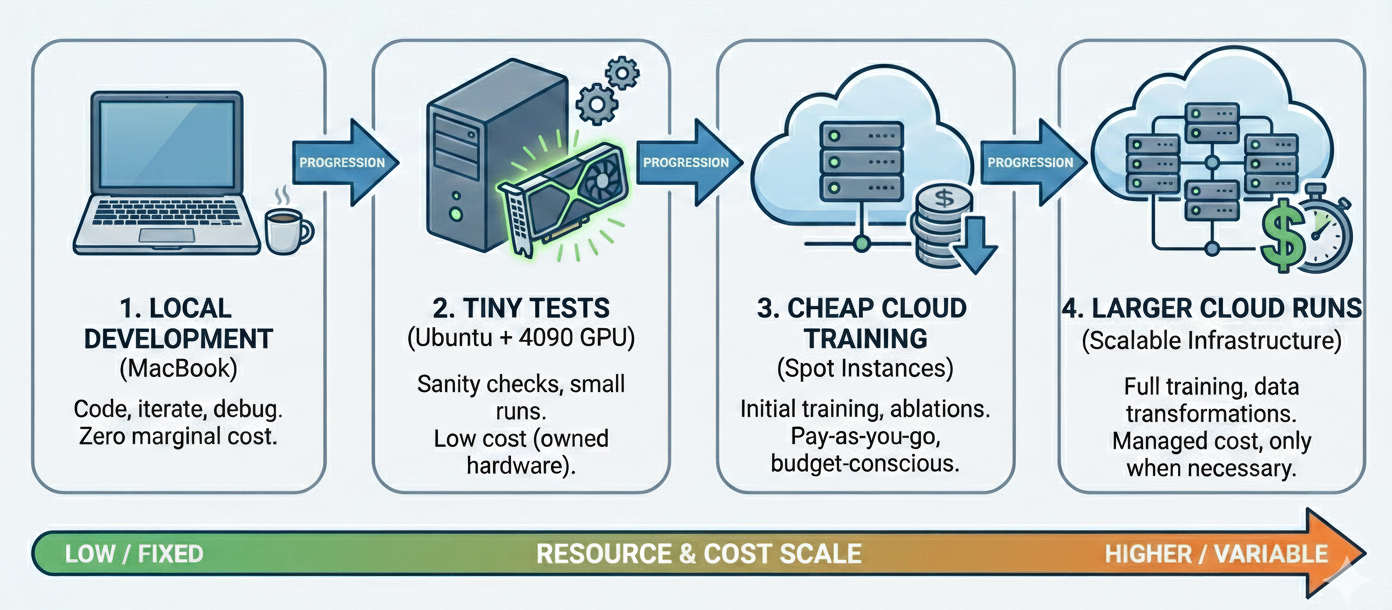

My development process looks like:

- Develop locally on MacBook

- Do tiny training tests/runs on my Ubuntu machine w/ 4090 card (if needed)

- Training run on cheap cloud GPU machines

- Larger training in cloud (moar GPUs)

This is, if nothing else, a way to keep things super economical and cheap! We are 100% bootstrapped and don’t have VC money to burn on GPUs.

Luckily our models are not huge (some run in realtime on CPU), but doing data transformations, scraping, and ablations can really add up if you aren’t careful.

Most of our models run in the 5-20 ms range and are generally under 10M parameters, though we have a couple of beefier exceptions.

I also can’t recommend highly enough using Cursor’s Remote SSH feature. For the cloud-based environments, being able to fire up a coding LLM to puzzle through NCCL errors or whatever derailed your latest training run is absolutely priceless.

❓What is causality, and why do we care?

Causal models exist in time, at a time t. They quite simply, use only the past data they’ve seen (like any $x_{t_i}$ where $t_i$ <= $t$), and no data from the future (no $x_{t_i}$ where $t_i$ > $t$).

So if you need a model to operate in realtime, you aren’t allowed to “cheat” by looking at information from the future.

The difference is stark: VJLab’s realtime stem splitter operating at ~90Hz is operating in a much different regime than an offline splitter like Demucs, which has access to the entire track and can take minutes to respond.

The truth is that most pretrained models are either for use in offline/batch situations, or simply aren’t performant enough for realtime audio, especially on CPU.

Thus we almost exclusively adapt or train new architectures from scratch.

But training your own causal models from scratch or adapting batch models comes with risks.

⚠️ The danger: Batch vs realtime

One of the banes of your existence if you train lots of these models will be causality. If your model has to operate like a human does (and cannot see the upcoming audio offline), you have to run inference and respond in time. Without seeing the future.

This becomes tricky when you want to train such a model, because you will have to train the model in batch (unless you have infinite patience and also infinite money).

This creates a dangerous situation where your training necessarily differs from your serving.

I have trained models that looked incredible performance-wise at train/test time in a batch setting, but fell apart when I fixed a causality bug or we finally got them deployed to a live inference setting or script. It’s an upsetting experience.

Remember: if performance looks too good to be true, it probably is.

⏱️ Timing constraints

Not only is causality tricky, but simple timing performance can be too.

If your model operates on new buffers of 512 samples, sampled at 44.1kHz, guess what, you can NEVER take longer than 512 samples / 44100 Hz ~= 11ms to respond! In fact a good rule of thumb is to keep your full buffer processing time to half your budget (ie: 5.5 ms).

Note that this time budget includes your forward pass and whatever pre/post-processing in C++ you need to do.

Even if your model has a lookahead period (ie: the model purposefully outputs values lagged slightly into the past), you still have a latency budget because new frames will just keep coming.

This is more vital on-device where you are pulling from an audio driver buffer, but in the cloud you don’t want to fall behind either.

😭 Examples of snags

Can it really be that bad?

What kinds of things might befall me, you might ask?

A few fun examples that definitely have never, ever happened to me:

- A bug in your training script reveals future labels to previous frame because your convolutions’ receptive field was large enough to include them from a future frame

- Your mean pooling operation aggregates over the time dimension (and is therefore not causal)

- You realize your model trains in batch on precomputed mels, but your streaming model has to compute them (and puts you over your latency budget)

- Because ONNX doesn’t support the FFT you hand-rolled your own convolutional FFT, but realized it’s too slow in realtime at the frame size you’ve chosen

- The SOTA pretrained model you blindly fine-tuned and is supposedly causal and realtime according to the paper authors … totally isn’t. You have fix the architecture and completely retrain

In short, a lot can go haywire if you aren’t careful.

The really awful part is: if you don’t realize a mistake like this until after you’ve finished your 3 day long training run, then you’ve just literally burned money.

To save yourself immense amount of time, money, and sanity, I highly recommend you have a consistent test for your dev & training environments.

🧪 Things you MUST test

You need an integration test of your model’s entire lifecycle:

Yes, really. Even if you’re just a researcher.

Even if your idea of MLOps is SSHing into your beautifully managed Slurm cluster with Weka FS access and running a script with accelerate.

Our integration test runs on any environment (macbook, linux single GPU, linux multi-GPU), in this order:

- Model latency test

- Runs the batch model against a batch_size=1 input

- Ensures non-accelerated Python version is close enough to latency budget

- Generating training dataset/metadata, if applicable

- Only tiny subset of data

- Generate sample outputs of data augmentation and labels, especially if your outputs are subjective and require a human sanity check

- Training + checkpointing

- In batch, of course

- Loading from checkpoint + resuming

- Can also add loading older checkpoints if backwards compatibility is desired

- Exporting model to accelerated format (ie: TorchScript, ONNX, or TensorRT)

- Running batch vs online equivalence test

- The MOST important step

- Match the outputs of your batch running alongside your realtime (streaming) accelerated model

- If you use mels in training and audio in realtime, yes, you must test the realtime with audio and do the mel transforms. Don’t be lazy!

- Ensure that output is same to a tolerance, ie: 1e-2 or whatever is necessary for your output domain

- Keep in mind the acceleration process will often introduce floating point or numerical differences, and that’s okay

- Outputing visual or auditory examples that can be manually inspected is really helpful

All of this logs to Weights & Biases and reports back a link to check the results from.

And trust me, if you can run it each time your node starts up, or as a pre-commit hook, you will thank me later. Or your manager will.

And in the age of coding agents, there really is no excuse not to ship this testing code, even if it’s quite a few LOC.

You could literally feed this post in as input and probably get a decent starting point!

𝍔 Platform differences

One obvious call out is you won’t be able (or need) to run every step the same on every environment.

Some example differences:

- Local development machines may run smaller toy versions of the model due to RAM, VRAM, or even MPS-specific constraints

- Exporting accelerators depends on the platform: exporting your torch model to TensorRT won’t happen on Mac OS X, for example

- Environments with different compute scales: running single GPU (

python train.py) vs multi-GPU (torchrun) vs multi-instance-multi-GPU (torchrun,ray, etc)

None of this is particularly surprising or revolutionary.

📓 A few other tips

- Unify your training and realtime model

- Do this by keeping input tensors in batch format at all points in the graph

- This allows you to make your realtime (exportable) torch module a simple wrapper of the batch training model where you set batch_size=1 and also handle state input/output

- Think about stateless inference

- Remember most all accelerated model formats and serving techniques are stateless

- You’ll need to hand back in state like previous mel frames, KV caches, LSTM hidden states, etc manually - your model can’t use logic internally to update state.

- Just ask

- Asking a top-tier coding agent to try to poke holes in your testing strategy or model architecture to find causality issues ahead of time is well worth your money and effort, even if the true positive rate is 10-20%.

- Avoid

BatchNorm!LayerNorm,GroupNorm, orInstanceNormare your (causal) friends!BatchNormtechnically “cheats” in training if your frames are temporal by looking at future frames to compute mean/variance stats to normalize inputs in previous frames- However. This violation of causality isn’t actually terrible for deploy-time inference, per se. This is because in a model frozen for inference (same as

.eval()mode), the mean/variance stored in theBatchNormop are frozen. - So your model will work just fine in production! But it will derail you when you run your streaming test to verify batch and streaming are the same, because they won’t be!

- And if you write off the difference as “oh that’s just

BatchNorm, let’s ignore the batch vs streaming discrepancy”, you might miss a real causality issue. This is the true danger ofBatchNorm

- However. This violation of causality isn’t actually terrible for deploy-time inference, per se. This is because in a model frozen for inference (same as

- Start with a single script 😱

- Sometimes in the research phase I will keep the entire new model in a single

train.pyas long as I can. Horrendous, I know. - Coding LLMs seem to do quite well with this, as a bonus

- Anything re-usable I factor out as soon as I can + add unit test, so other models in future can benefit

- Once the model is working end to end from train to accelerated realtime, then I move models into proper Python modules for reusability, class composition, and so on

- Sometimes in the research phase I will keep the entire new model in a single

- If your model needs an FFT during inference, think carefully about how you train

- For example, ONNX doesn’t support

torch’s FFT or iFFT operation - The platform you deploy to (OS X, Ubuntu, Windows) will determine the fastest way to compute the FFT, but beware, not all FFT routines have the same scaling. For this reason, we usually choose

libtorch, which supportstorch’s FFT routines - You should always try to transform your model to an accelerated format/method that keeps your train/deploy equivalence intact or your will run into problems

- Some FFT libraries, while fast, are not licensed well for commercial use

- For example, ONNX doesn’t support

🔊 In closing

Truly realtime audio is tricky! And often your first question should be: does this even need to be realtime?

Many features you might imagine could just be done quickly (but in batch), and save you the headache.

But when you do truly need it, make sure to keep your eyes open for issues like these, and put a strong integration testing framework in place to prevent you from wasting time and money.

Happy training & testing :)